Standing in a repurposed warehouse on the outskirts of Belper in the East Midlands, the British boss of one of the country’s largest makers of gas-fired boilers is watching dozens of engineers assembling one of its newest products, which should have a crucial role to play in the fight against climate change.

Henrik Hansen, Vaillant’s UK managing director, has overseen a two-year, £50mn investment to convert the building into a factory to produce the German company’s Arotherm heat pump.

Yet he has not seen demand pick up as quickly as his employees have learned the skills to assemble the new type of heating system that environmentalists and most policymakers believe are crucial to decarbonising Britain’s 30mn households. Domestic boilers account for about 14 per cent of the country’s CO₂ emissions.

“We’ve had people with very long service eager to learn new technologies,” Hansen said. “It’s been very impressive.” But the market, he added, had been “a lot slower than we anticipated”.

Successive governments have backed heat pumps to replace gas boilers as part of the UK’s goal of hitting net zero by 2050 because the devices run on electricity, which is increasingly generated from renewable sources, such as the wind.

But in September, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak watered down the messaging as part of a series of retreats from measures aimed at tackling climate change. The dilution of green targets came as the ruling Conservatives began to worry about the impact of the mounting costs of green policies on voters ahead of a general election.

On Wednesday, the Climate Change Committee, the government’s independent climate advisers, said that ministers’ plans to make the UK resilient from climate change fell “far short” of what was needed.

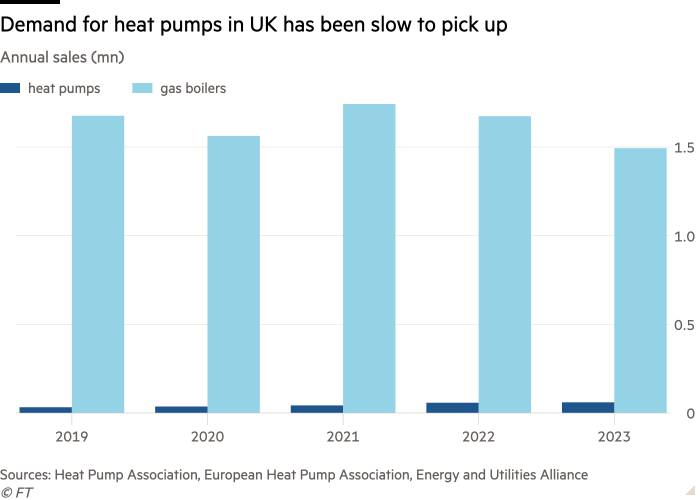

Demand across the nascent UK heat pump sector has been sluggish. More than 60,200 heat pumps were sold in Britain last year, a 4 per cent increase on 2022, according to the Heat Pump Association trade body. That is a long way from the 600,000 annual installation target the government wants to hit by 2028, and is dwarfed by the 1.5mn gas-fired boilers sold last year.

The low volumes mean the pumps cost significantly more than gas boilers, even before their higher installation costs, which can include other expensive changes to the home such as new radiators and improved insulation.

A government grant, which was increased by 50 per cent to £7,500 in September, is available to retrofit homes against an all-in cost that can range from £7,000 to £17,000 for a two-bedroom property to between £13,000 and £30,000 for a four-bedroom house.

Ministers have described the grant as the “most generous in Europe” with more than 33,000 applications received by the end of January, according to official figures.

Yet industry executives said that hitting the ambitious 2028 installation target required clear signals from the government that it planned to stick to its proposed phaseout from 2035 of sales of all new domestic heating systems that used fossil fuels.

“Anything that creates a lack of certainty is always a problem for the market because it can give all players cause for pause,” said Hansen.

Sunak’s backtracking last year included delaying a planned ban on new oil- or LPG-fired boilers for rural homes not connected to the gas grid from 2026 to 2035. That announcement cast doubt on another proposal that was under consultation for a similar ban on gas-fired boiler installation in new builds from 2026.

The low demand for heat pumps is also expected to see the government bow to fierce lobbying by gas-boiler makers to delay plans to impose fines on them from next month unless a certain proportion of their output is heat pumps.

Russell Dean, residential group product director at rival heat pumpmaker Mitsubishi Electric, echoed Hansen that a consistent message was needed. “Certainty allows us to invest at the right speed . . . Every technology will say — please give us certainty and we will invest all the money that we can.”

The government said it was committed to its 600,000 heat pumps target by 2028 but wanted to do that in a way “that does not burden consumers”.

It added: “This means giving families more time to make the transition, ensuring they only need to switch to a heat pump when their boiler needs replacing from 2035 — saving families thousands of pounds.”

But there is no legislation in place to confirm the mid-2030s switch off, which the government has so far only termed an “ambition”. Sunak in September further undermined the idea of an eventual ban when he said households who found the transition “the hardest . . . [would] never have to switch at all”.

Another hurdle to demand is the running costs of electrical heat pumps. The structure of Britain’s energy market means levies designed to fund the build out of renewable energy generation are built in to the cost of electricity, making it more expensive per unit of energy than gas. “If you remove those, you can open up a much wider market,” said Chris Galpin, policy adviser at the E3G think-tank, and a former government policy adviser.

Octopus Energy, one of the biggest energy suppliers in the UK, has recently expanded into heat pump manufacturing and is planning to build a factory either in the UK or continental Europe.

The final decision will be heavily influenced by the investment climate, said Alex Schoch, Octopus’s head of flexibility, a part of the business focused on the energy transition. “A lot will depend on whether we see the right market signals and government policy continuing in the direction of heat pumps,” he said.

Despite the challenges, Hansen remains optimistic. “If you take a step back and look overall at what has happened in the last five years, there is a significant increase in heat pumps everywhere,” he said. “It is possible to transform.”

Additional reporting by Lucy Fisher

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here