Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Who wants to do their banking where they buy their bread? Not many people, judging by the flight of Britain’s supermarkets from financial services.

Sainsbury’s has announced a “phased withdrawal” from its banking business. Tesco is also reportedly seeking a buyer for its bank for about £1bn. The UK’s biggest grocer already sold off its mortgage book in 2019.

Their retreat should serve as a salutary lesson to companies that believe they can use their brand to conquer other capital-intensive sectors.

Both Sainsbury’s and Tesco moved into banking in 1997, initially via joint ventures with established banks. The logic appeared sound enough: traditional banks were struggling with large, expensive branch networks. Supermarkets could poach customers via a phone line and low-cost kiosks in stores.

There were early warning signs, though. Just months after launch, Tesco had to compensate customers who suffered long delays setting up their accounts. It had to hire more staff to deal with inquiries.

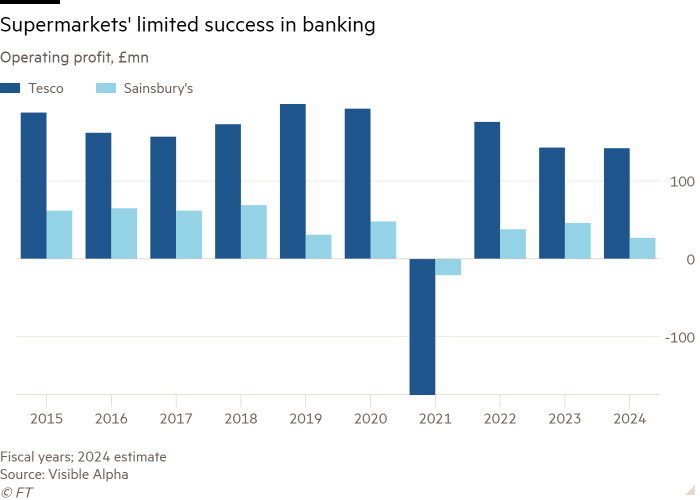

In 2008, just months before its partner was nationalised, Tesco bought out Royal Bank of Scotland — now NatWest — for £950mn. It confidently declared it could generate £1bn of profit annually from services including financial services and telecoms. Tesco Bank never came close. It is forecast to generate operating profits of about £142mn this year, according to Visible Alpha, barely changed from 2023.

As UK challenger banks know too well, building a financial services business of scale requires huge financial and human capital. Given that the same is needed to maintain core food businesses, Sainsbury’s and Tesco banks never broke through, says Clive Black of Shore Capital. Sainsbury’s Bank has less than 5 per cent share of UK consumer lending, reckons RBC Capital; Tesco is marginally higher at 5 to 6 per cent.

Cross-selling financial services to loyal grocery shoppers was probably doomed, given the longstanding failure of banks to flog other services to, say, current account holders. The idea that lenders such as Barclays or HSBC, among those reportedly bidding, would now see great potential in cross-selling to supermarket customers should be treated with scepticism.

Sainsbury’s tried to sell its bank in 2021 and failed. And these are small morsels. Lex’s back-of-the-envelope calculations, based on sector price/earnings ratios, suggest a valuation of perhaps £100mn for Sainsbury’s Bank and under £600mn for Tesco.

When he joined Sainsbury’s in 2020, chief executive Simon Roberts declared that the retailer would go back to basics and focus on its food business. The shares are since up 18 per cent versus a 5 per cent decline in the FTSE 100 index.

Others, such as John Lewis, which have suggested they can use shoppers’ brand affection to find success in unrelated sectors should take note.

Lex is the FT’s concise daily investment column. Expert writers in four global financial centres provide informed, timely opinions on capital trends and big businesses. Click to explore