“We have the expertise, the supply chains and the teams ready to build Hinkley Point C safely, on time and on budget,” Vincent de Rivaz, then chief executive of EDF, said in 2016 as the project to build the UK’s first nuclear power station since the 1990s got under way.

That confidence has proven misplaced. Earlier this week, the French state-owned utility announced the latest in a series of delays and cost overruns to the 3.2 gigawatt plant under construction in Somerset.

The setback to a plant that is meant to supply electricity to 6mn homes has raised fresh questions about the UK’s energy strategy and its push to decarbonise the grid over the next decade as part of its goal to reach net zero by 2050.

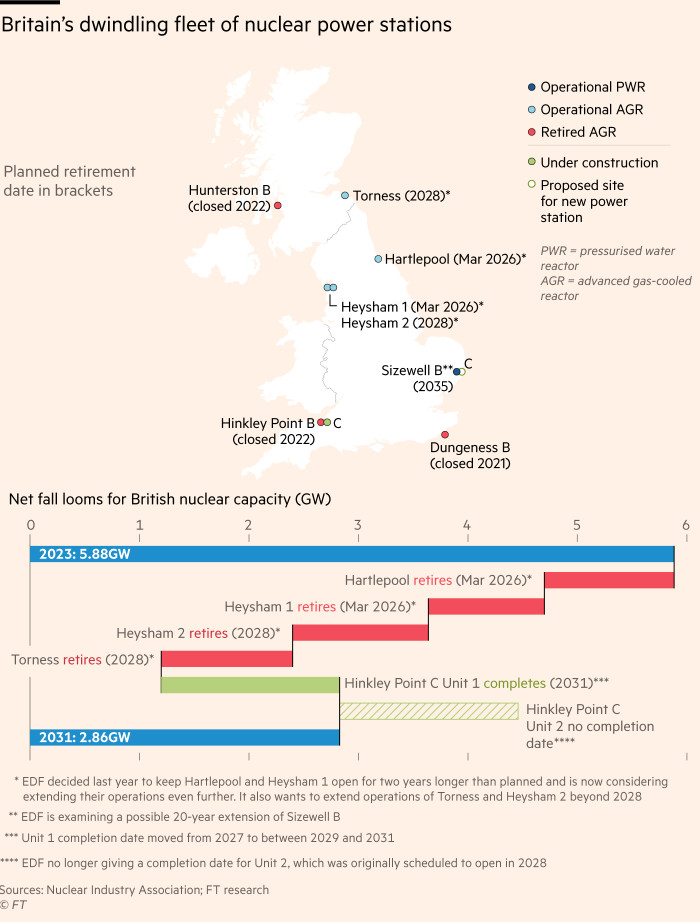

A new generation of nuclear power stations forms a crucial part of the government’s decarbonisation drive with plans to build up to 24GW by the middle of the century up from 5.88GW at present.

“Nuclear energy is a key element of the UK’s transition to a net zero power system,” said Simon Virley, head of energy at KPMG in the UK. “If we fail to build the necessary capacity, any gap is most likely to be filled by gas, thereby making it harder to get to a net zero power system in the planned timescales.”

Hinkley Point C is the first of what ministers hope will be a new generation of nuclear power plants that will replace and expand on the output from what remains of Britain’s ageing nuclear fleet, which EDF owns and operates in a joint venture with Centrica.

The fleet supplied about 14 per cent of the UK’s electricity in 2022 but four of the five plants are set to close by March 2028, while demand for electricity is expected to grow as the economy switches away from fossil fuels.

Analysts have warned the gaps left by nuclear generation could push power prices up towards the end of the decade, as gas-fired power plants, which tend to provide expensive back-up electricity to the grid, would need to step in.

“It’s important not to disassociate energy security and energy affordability,” said Rob Gross, director of the UK Energy Research Centre. “If we are more reliant on gas and if gas continues to be expensive then electricity prices will tend to be higher.”

The first of Hinkley Point C’s two 1.6GW reactors, previously due to start producing power in 2027, could now be delayed until 2031. EDF is no longer giving an in-service date for the second unit, as cost of the whole project has ballooned to as much as £46bn in today’s prices.

Analysts at LSEG estimated the latest delays to the plant would push wholesale power prices up by as much as 6 per cent between 2029 and 2032, based on the assumption that unit two would come online in 2033.

“If you take a big power station out of the supply side and you want the lights to stay on — it’s not going to be a suppressant on power prices,” added Martin Young, an analyst at Investec.

EDF is looking at ways to help mitigate the latest delay. Two weeks ago it said it was examining plans to further extend the life of its four oldest plants, which use advanced gas-cooled reactor technology and date back to the 1980s.

But there is still some doubt about that plan. Jerry Haller, EDF’s former decommissioning director, told a parliamentary committee inquiry in 2022 that nothing could be done to extend the life of the AGR fleet again. “No further investment will take them further,” he said at the time.

EDF said since those comments further inspections of the reactor cores had “been better than, or in line with, our expectations”. It had already decided last year to keep two of the plants — Heysham 1 and Hartlepool — open until at least 2026.

But even if more life can be eked out of existing reactors, the problems besetting Hinkley Point C have raised wider questions about how the UK will reach its 24GW nuclear build target by 2050.

EDF had said previous delays to Hinkley were due to disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic. But this time, the French company, which has encountered similar long delays on two other power stations in Europe that use the same technology, put the setbacks down to engineering problems.

The only other proposed large UK nuclear power station will be a near copy of Hinkley Point C at Sizewell in Suffolk. EDF and the UK government are in the process of trying to raise funds from outside investors to build it at an estimated cost of £20bn.

Unlike Hinkley Point C, where EDF bears the risk of cost overruns — an issue the French state is putting pressure on the UK to help with — Sizewell C’s financing model will see bill payers exposed to some of that risk instead. Nevertheless, EDF’s record on delivery could make prospective investors wary.

The government is also planning to back several companies developing new types of miniaturised nuclear power plants, dubbed small modular reactors, with the first contracts expected to be awarded later this year.

But SMRs can only fill some of the gap and the most pressing challenge is to hit the government’s target of having all electricity generated by low-carbon sources by 2035 (or 2030 should the opposition Labour party win the general election later this year).

“The UK needs nuclear as part of its power generation mix as we move to a system based largely on renewable sources,” said Sir John Armitt, chair of the National Infrastructure Commission.

“Hinkley Point C should still be able to make a contribution to the government’s target to decarbonise the power grid by 2035, but the chance for any additional major plant doing so is at risk unless we can learn from Hinkley in order to build future plants more quickly and efficiently.”

The government said it remained “confident” it had the “right energy mix”, adding that its “road map setting out the biggest expansion of nuclear in 70 years . . . [would] help us meet our ambitious targets to deliver up to 24GW of low-carbon nuclear energy by 2050”.